Hard work pays off for ol’ marble eyes on Lake Winnebago.

by Lisa Gaumnitz:

Twenty years ago walleye fishing on Lake Winnebago stunk. Literally.

Scant rain and snow in the late 1980s dried up walleye reproduction and the fishing with it while goosing the growth of smelly algae blooms, recalls Mike Arrowood, a 40-year resident of Fond du Lac.

“My kids used to call it Winneseptic,” he says.

What a difference 20 years make. Today, the state’s largest inland lake is significantly cleaner and clearer and fishing for ol’ marble eyes is “superb,” says Arrowood, chairman of the board of directors of Walleye for Tomorrow. “Most anybody can fish on Winnebago now and catch walleye.”

This frying pan favorite’s natural reproduction in the past decade overall has been the best it’s been in a generation, providing fishing opportunities for local residents, destination fishing for out-of-state aficionados, and an annual $234 million economic boost for the five counties surrounding Lake Winnebago and the other lakes in the Winnebago system – Butte des Morts, Winneconne and Poygan.

The secrets of that success?

Arrowood and state fish biologists point to three main factors:

- The Department of Natural Resources, local governments and citizen groups have successfully implemented the lion’s share of a 1989 comprehensive management plan aimed at improving fish and wildlife habitat, water quality and user issues in the system.

- Citizen groups like Walleyes for Tomorrow, Otter Street Fishing Club, Shadows on the Wolf and others have stepped up to protect, create and restore habitat. They’ve poured in hundreds of thousands of hours of labor, donated millions of dollars for equipment and supplies or secured such at a reduced cost, and jawboned local officials, private property owners and industry to take measures benefitting walleye production.

- The Department of Natural Resources and partner groups have pursued an aggressive research program to unlock the secrets of walleye in a vast, everchanging system, to work together to apply that knowledge and to be committed to it over the long term.

“One of the things I tell the public is, keep your eyes on the prize,” Arrowood says. “The other thing I tell the public is, if you put a quarter-inch fry in the lake, it’s going to be a while before it’s in your frying pan.”

A guidebook and template for improvement

Lake Winnebago’s 137,708 surface acres make it by far Wisconsin’s largest inland lake – Petenwell Lake in Juneau County is next at 23,000 acres. Add in other Winnebago pool lakes and you’re at 17 percent of the state’s inland surface water acres, not to mention the Wolf and Fox rivers that connect them.

Two million people live within 75 miles of the lake and have turned it into the second most popular fishing lake in the state. Lake Winnebago supplies drinking water for Oshkosh, Neenah, Menasha and Appleton as well as many small communities. It is the source of water – and waste assimilation – for local industries and drains a geographic area six times the size of Rhode Island.

By the late 1980s water levels kept artificially high by the navigation system maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers contributed to aquatic plant loss, greater erosion and increased sediment, which all harmed water quality and habitat. Smelly algae blooms were a problem. A drought left walleye spawning marshes on the Wolf and upper Fox rivers dry and resulted in years of very poor walleye reproduction, leaving a big hole in the fish population and prospects of poor fishing for years to come.

Local citizens turned out in 1986 for public meetings to share their concerns about the lakes. DNR staff used that information and feedback from community leaders, and then worked with the leaders to develop strategies to address the concerns. In 1989, the resulting Winnebago Comprehensive Management Plan was approved with 120 strategies to improve fish and wildlife populations and habitat, water quality, and management and use of the water resources.

Cooperative habitat projects have played a key role in rebuilding walleye and sauger populations.

Photo courtesy of Mike Arrowood“The plan put all of this stuff under one roof,” says Art Techlow III, a senior fisheries biologist who has coordinated plan implementation. “It is a living, dynamic plan. We purposely made it short and easy to read so that people could handle it, understand it and do it.”

The number of priority watersheds – those in which the Department of Natural Resources provided counties with grant money to work with farmers and municipalities to curb runoff – grew from one to 10 in the land area draining to the lakes.

The department pursued large-scale habitat projects to install massive breakwaters to protect aquatic plants, control erosion and improve water quality. Winnebago County and other local governments pursued similar but smaller habitat- focused projects, often getting DNR funding and permitting help. Many local governments and conservation groups used the plan as a reference to identify and guide which projects they pursued, Techlow says.

“The thing that has had the most lasting impact is the willingness of both the public and DNR personnel to sit down together and discuss the issues and possible solutions,” Techlow says.

A few years ago he filed a progress report noting that 70 percent of the 120 strategies had been completed, were in progress, or had been adopted as part of the agencies’ or groups’ annual duties. “Wherever we’ve done projects we’ve been very successful in improving water quality and desirable fish and wildlife populations and building habitat,” he says. “Everything you do that’s positive will eventually add up to something of significance.”

Kendall Kamke, a senior fisheries biologist who’s worked on Lake Winnebago for 20 years, sees it every day. “We’re still at the mercy of water levels dependent on Mother Nature when it comes to walleye production, but we’re in a much better position to maximize production in those high water years,” he says. “And if I had to point a finger and ask, ‘this is what was really instrumental for the success of today’s walleye fishery,’ I’d say it’s the habitat work that’s been done and continues to be done as a result of that comprehensive management plan.”

A focus on habitat

The management plan and poor walleye fishing in the early 1990s helped focus the attention of conservation-minded citizens in the area. “We decided there should be something we can do to boost walleye production,” Arrowood says.

So the Winnebagoland Muskie Club, Lighthouse Anglers, Eagles Anglers and the Winnebagoland Conservation Alliance came together in 1991 to start Walleyes for Tomorrow. Its mission was to work with other clubs, agencies and the Department of Natural Resources to improve the quality of walleyes and sauger on the system. And the group would achieve its goals through broad strategies including supporting water quality and habitat improvement, building or improving spawning areas, stocking, research, education and advocacy.

With $5,000 in seed money from Mercury Marine and another few thousand in the bank from its first banquet, the fledgling organization asked DNR fisheries staff what would be a good project for them to begin.

The answer was the Eureka Dam, a low-head navigation dam on the upper Fox River. Not only was the dam blocking migration of walleye, sturgeon and other species up and down the system, but the backwash, or “boil” created behind the dam churned up and ground down walleye fry trying to make it downstream.

Walleyes for Tomorrow, working with Sturgeon for Tomorrow, was able to marshall $108,000 in donated materials, labor and funds to “fill in” the boil with rocks. The one-time walleye fry death trap gave way to gentler rock rapids and young walleye have since been surviving the ride in good numbers.

The group turned to building, enhancing and rehabilitating spawning marshes along the Fox and Wolf rivers to get the increased walleye production they wanted. They worked with private landowners to allow the club, its contractors or the Department of Natural Resources to do work on their land to bring flowing water back to the marsh. They mowed the brush, replaced smaller culverts with bigger ones, and cut down steep river banks to allow flooding into the marshes during spawning time.

“The spawning marshes are the lifeblood of the Winnebago system,” Arrowood says. “A female walleye won’t go into the marsh unless there’s flowing water and the walleye fry that hatch can’t swim so they need flowing water to take them back out.”

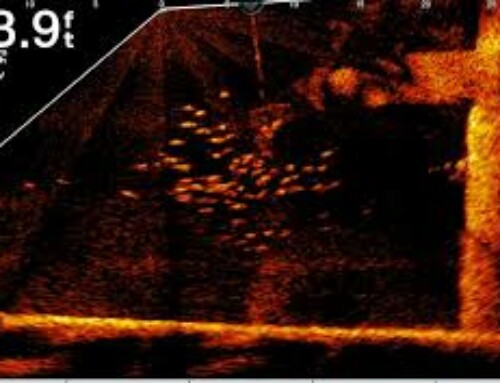

They have completed 22 such projects on the Fox River and 24 on the Wolf River in the last 20 years, and have funded and installed 154 rock habitat structures in the lakes. Members hauled 75 to 250 tons of rock for each structure onto the ice where they would eventually sink to the lake bed and provide habitat for walleye, other fish and their prey, Arrowood says.

Since those early days, Walleyes for Tomorrow has expanded to 15 chap ters in Wisconsin and one in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Through chapter banquets and other events, the organization raises about $200,000 a year and devotes that money to projects statewide.

While Walleyes for Tomorrow is the biggest organization operating on the entire system, other clubs have played key roles in specific system waters. Shadows on the Wolf, Lake Poygan Sportsmen’s Club and the Otter Street Fishing Club are among the large and active ranks of conservation groups aiding fisheries. Sturgeon for Tomorrow, while focused on sturgeon, also contributed to habitat improvement projects that benefit multiple species.

They’ve had more success than the Department of Natural Resources in getting cooperation from private landowners, securing reduced costs for supplies, and raising money for worthy projects that may suddenly arise, Kamke says. For instance, last year when the department wanted to put sonic transmitters in 100 walleye to track their movements, Kamke had no funding set aside for the project. A few calls to club leaders and two to three weeks later, the Department of Natural Resources had the entire $32,000 needed to buy the transimtters and make the project happen.

“It’s just a joy to work down in this area of the state because the fishing clubs really get involved and help DNR staff with not only labor, money, management and advocacy, but everything,” Kamke says.

“The appreciation is mutual,” Arrowood says. “I can’t say enough about the Department of Natural Resources. They’ve bent over backwards to help us with everything.”

Research unlocks secrets

Conservation groups’ funding and labor is key for walleye research on the system.

“Because of Lake Winnebago’s size, complexity and heavy angling pressure, we need the most current information possible to manage the system to its full potential,” Kamke says.

Walleye behave differently on the Winnebago system. “There is nothing textbook about the whole system, with the fish spawning on grass marshes,” he says. “It’s not what you learn in school about classic walleye behavior where they spawn on rocky shorelines on the north and west side of lakes.”

There’s been a flowering of research in recent years thanks in large part to the $13,000 education grant Walleyes for Tomorrow gave to fund the graduate school research of Ryan Koenigs.

Koenigs, who also received funding from the Sheboygan Walleye Club, has provided ideas and manpower to answer important questions posed by fish managers and by anglers who attended summer 2010 meetings on Winnebago walleye management. Top concerns for anglers across all meetings were overharvest, especially during the spring run; vegetation and water clarity and impact of those on the fishery; and the impact of tournaments.

As of February 2012, projects are underway or wrapping up to investigate most of those concerns – and a few others that proved hot buttons at specific 2010 meeting locations.

To respond to anglers’ concerns at the Shiocton meeting, the Department of Natural Resources worked with Fred Binkowski at the University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee WATER Institute to investigate whether the department’s method of capturing walleye for population surveys affected survival of adult fish and their offspring.

DNR crews often use boats equipped with probes to deliver a small electrical current to the water that temporarily stuns fish so they can be netted, measured, tagged and returned to the water. The other main capture method involves setting large hoop nets, or fyke nets, that act as funnels to trap swimming fish.

DNR crews empty fyke nets of fish that will be measured, tagged and released.

© DNR FileIn a head-to-head comparison in 2011, Koenigs reports that no discernable differences were found in adult fish survival nor in the hatching, survival or growth rates of their offspring. Fyke nets, in fact, appeared more problematic for crowding and stressing fish, and in some instances, loss of protective slime, leaving fish more vulnerable to infection.

To check concerns about tournaments and overharvest in general, DNR seasonal employees stationed at popular boat launches asked recreational anglers about catch rates and the department pulled and monitored several fishing tournament records. Of the 73 permitted tournaments on the lake in 2011, 39 were for walleye, with most of the larger tournaments catch and release. Their findings show that contrary to popular belief, tournament anglers have a very insignificant impact on walleye populations. If there is any effect from harvest, it is due to recretional anglers.

Male fish were heavily harvested in the spring as anglers left the big females to spawn. But after the spawning season and into the summer, female walleyes were heavily harvested by anglers, findings at which the Department of Natural Resources and conservation groups will be taking a closer look.

Research also investigated the accuracy of the standard methods the Department of Natural Resources and most fish agencies use to mark fish and determine fish age.

Koenigs and colleagues concluded that the plastic, spaghetti-like “Floy” tags they insert by fishes’ dorsal fins come out within one year of tagging in 21.9 percent of the fish. That’s a concern because the tags are critical in tracking fish movement, population size and angler harvest or exploitation rates.

Likewise, a study to understand the accuracy of determining fish age by counting the rings in a cross section of a fish’s dorsal fin found that methodology was less accurate with older fish.

Koenigs says, “By underestimating the age of older fish, we were overestimating natural mortality. This is important because if management believes natural mortality and mortality due to angler harvest are competing causes of death, they might ask ‘If the fish are going to die anyway due to natural death, why not let anglers harvest those fish?’, leading to overfishing of the stock.”

Koenigs says these findings do not mean that the Department of Natural Resources or other agencies should abandon using Floy tags to mark fish or dorsal spines for aging – but that they understand the effects of tag loss and aging error on management of the populations and strive to collect accurate data. Floy tags are less expensive than the microchip tags the department uses in some instances, and a newer, more accurate measure of aging – counting rings in fish otoliths, or ear bones – requires killing the fish to remove the ear bone for age estimation.

Answers to burning questions and why fish don’t bite

For anglers, perhaps the most important research answers the question, “If walleye reproduction and numbers are off the charts why is fishing sometimes so slow?”

Koenigs looked at harvest rates for walleye, abundance estimates for forage fish like gizzard shad, and assessments of the size and weight of fish from surveys from 1993 through 2010. He found that when forage fish populations are high, walleye aren’t biting what anglers are selling, so anglers catch fewer walleye.

“Fishing wasn’t bad in 2010 because there were no walleyes in the system,” Kamke says. “It’s because there was so much forage that walleyes just had to turn their heads to eat.”

When that happens, Kamke says, walleye anglers will want to change tactics and hope to hook into some active fish, or switch and fish for other species, such as bass or panfish, both of which are also increasing in numbers, with the knowledge that next year is likely to be a different year.

“While that doesn’t make it any better that year, the high forage base means the fish that aren’t biting this year will be bigger next year. You could be staring at a monster on the other end of the line.”